Chaos is a natural by-product of innovation. Innovation happens best in conditions of upheaval, disturbance, and dissonance. However, people expect their leaders to keep things calm, predictable, and orderly. How do we coax order out of chaos without squelching innovation?

Stages of Innovation

Innovation occurs in predictable stages. It begins with a disturbance in the status quo, which the organization often tries to ignore or resolve. Eventually, the disturbance escalates into disruption, where it can no longer be ignored. As old processes and structures disintegrate, the organization enters into innovation and learning about its new environment. Eventually comes the emergence of new organizing principles and structures. Finally, the organization integrates what is novel into what it knows already—and finds coherence and a fresh identity.

For years, a congregation has been spending more than it takes in, dipping into its endowment fund to cover the gap (disturbance). To save money, the congregation has neglected to maintain its building. Suddenly an antiquated boiler explodes, and the church doesn’t have the funds to replace it (disruption). Finally the congregation acknowledges it can’t afford to stay in the building. A buyer is identified, and the congregation begins to imagine ministry unencumbered by building ownership. They explore various options that involve rentals, mergers, and new models of church (innovation). After a chaotic year of waiting for clear direction, leaders discern a pathway forward (emergence). The church chooses to reorganize around a house church model (coherence).

Engaging Emergence

Emergence, one stage in the innovation process, is new order arising out of chaos. As people interact in conditions of upheaval, chaos eventually and naturally yields to order. Organizations gravitate towards order over chaos. A galvanizing idea or principle is introduced. Individuals act and react to the idea until new structures and processes begin to crystalize.

Emergence is not a controlled process and cannot be imposed by an authority figure. It is a self-organizing process that feeds on experimentation, risk taking and learning from failure. It is messy and anxiety producing. Emergence doesn’t begin with the clearly articulated vision of a leader, followed by the careful execution of goals and action plans. The well-meaning leader who steps in to manage the chaos may inadvertently squelch innovation.

Five Practices

A leader cannot control the pace or direction of emergence. However, she can take purposeful action. A leader can attend to all that is arising and coax new order out of the chaos—when the group is ready. Five core leadership practices support the natural arising of order out of chaos.

1. Foster Experiments

Emergence depends on learning, and experiments are a great way to foster learning. Running many small experiments with minimal risk is better than taking on a few big risks. Small experiments provide more opportunities for learning and allow for rapid course corrections.

Experimentation happens best when diverse people frequently encounter one another. A leader can increase the opportunities for people with diverse viewpoints to connect and interact, eliciting new ways of thinking and behaving.

A leader can foster a propensity for action over inaction by empowering people to solve problems that they care about, rather than just asking people to accept and occupy positions. Positions people are not interested in can remain vacant. Old ways of authorizing and deciding must give way to nimbler modes of decision making.

An effective leader provides an umbrella of protection for innovative ideas to germinate and grow before they come into the central life of the organization. Sometimes ignoring a creative experiment for a while is the best way for a leader to support it. Paying attention too soon may draw too much attention to a seedling idea that needs more time to root.

2. Embrace Failure

Failing forward is a critical skill in nurturing emergence. Congregations are biased towards planning and against evaluation. We plan, we may act, and then we plan some more. But we don’t stop to assess where we have been. When we fail, we put a positive spin on the failed attempt and move quickly on to the next action.

Over time, this creates an allergy to failure. We fear investing our resources into anything that might fail, and so eventually our experiments grind to a halt.

Failure is a necessary consequence of innovation, because failure is always a possibility when we are doing something new and unexpected. With every outcome, we learn what doesn’t work, which brings us one step closer to discovering what might.

3. Replace Repetition with Iteration

Repetition and iteration both involve doing something again and again. Repetition is static, we repeat the same action each time in response to a stimulus. If I do X, it will result in Y. Unfortunately, repetition doesn’t yield much learning.

Iteration is a kind of repetition in which each action influences the next. Because of what we learn, we try something new next time. The new action often rhymes with the last—but with an intentionally nuanced difference. We integrate what is novel into what is known.

Innovation requires us to learn new responses to changing conditions. Instead of repeating the past, we iterate.

4. Name What is Arising

During emergence, we can’t be clear about outcomes. However, we can remain crystal clear about our intention. We can remind people what we are trying to learn. We can talk about what matters most to us—our core values. We can emphasize what we do know about our current mission and ministry.

As emergence begins to cohere into something meaningful, we can name what is arising. Naming something is a sacred act. Moses stood at the edge of the promised land and retold his people’s story. He named them as the people of the covenant, God’s chosen nation. He linked their past with their present and their future. This is what effective leaders do. They tell the story as it unfolds.

5. Wait for Simplicity on the Other Side of Complexity

Emergence often involves an intuitive leap in practice, a major disruption from the past. Months or years of small incremental changes then follow the initial disruption, like ripples in a pond after an initial splash. Smaller, incremental changes strengthen the innovation.

It is tempting to respond mainly to the initial splash by laying out a clear solution to our problems. When that large discontinuous interruption occurs, we want to jump on board, announcing that a new beginning is upon us.

It is better, though, to pay attention to the ripples for a while before declaring that a new direction has been found. The initial splash muddies the waters with complexity. As the ripples dissipate, simplicity emerges.

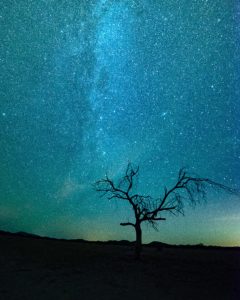

Waiting for order to emerge from chaos is not for the faint of heart. It requires patience and forbearance—especially of leaders. But we can still lead while waiting by remembering the stages of the innovation process: Nurture a climate of experimentation and a bias towards action. Embrace and learn from failure and success. Name what is arising. Wait for simplicity, while pointing people towards the future that is still emerging.

Susan Beaumont is a coach, educator, and consultant who has worked with hundreds of faith communities across the United States and Canada. Susan is known for working at the intersection of organizational health and spiritual vitality. She specializes in large church dynamics, staff team health, board development, and leadership during seasons of transition.

With both an M.B.A. and an M.Div., Susan blends business acumen with spiritual practice. She moves naturally between decision-making and discernment, connecting the soul of the leader with the soul of the institution. You can read more about her ministry at susanbeaumont.com.