The change of a calendar year suggests inspiration. The old year with its depleted reserves is behind us. For leaders, a new year calls forth optimism and imaginative beginnings—or it should. But what if you just feel empty? What can you do when fresh vision eludes you, when you have lost capacity to dream on behalf of the congregation you serve? Is it time to leave, or is there a way to recapture the passion and vigor of a new perspective?

The change of a calendar year suggests inspiration. The old year with its depleted reserves is behind us. For leaders, a new year calls forth optimism and imaginative beginnings—or it should. But what if you just feel empty? What can you do when fresh vision eludes you, when you have lost capacity to dream on behalf of the congregation you serve? Is it time to leave, or is there a way to recapture the passion and vigor of a new perspective?

Undoubtedly, in the old year you read at least one book on church vitality. Ten Critical Steps Forward, or Three Things Every Church Must Do, or Five Mistakes All Leaders Must Avoid. You’ve heard of powerful transformations taking place in other congregations. Maybe you even tried some of their ideas. Inevitably, disappointment followed when something that worked elsewhere failed for you. You can imagine new ideas for ministry in other places, but a fresh vision for your congregation isn’t forthcoming.

Vision is a Way of Seeing

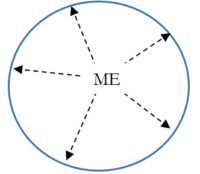

Figuring out what to do with your organization is not as critical as figuring out how to see it. Most of us picture ourselves at the center of the organization we lead. We understand how things work based on how people have responded to our past initiatives. This is a form of perceptual bias: If I say this, they will do that. If we try this, they will expect that.

David only sees a donor base interested in maintaining the status quo. Deborah only perceives a governing board clinging to an outdated building. Matthew only notices the crotchety group of parents who won’t entertain new ways of structuring a youth group.

David only sees a donor base interested in maintaining the status quo. Deborah only perceives a governing board clinging to an outdated building. Matthew only notices the crotchety group of parents who won’t entertain new ways of structuring a youth group.

We tend to believe that others are internally responsible for their own behavior—that something about their personalities or values or opinions explains everything about the way they act. We make this assumption because we are not fully aware of the external, situational factors that also shape their choices and behavior. In other words, we’re guilty of attribution errors.

Furthermore, because it is impractical to learn everything about the internal reactions of every congregation member, we make sense of our experience by using stereotypes.

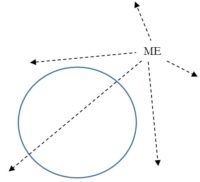

Seeing with a fresh perspective requires removing ourselves from the center of the equation and noticing what other people actually say and do without letting our own attributions, stereotypes, and habits distort the picture. It requires adopting a broader, more impersonal perspective, unencumbered by the learned responses that the organization and the leader have taught each other.

Vision Starts with Unknowing

Many people believe that organizational vision depends mainly on the imagination of its senior leader. The leader articulates the vision, defines pathways forward, and convinces others to come along.

This is one way organizations generate vision, but effective leaders often start not with their own imagination, but with unknowing. As leaders, we can rest in the assurance that a Presence is at work in the organization, a divine spark larger than our lived experience. When we set aside ego and personal agenda, a way forward emerges. However, the divine spark won’t reveal itself if we are too focused on one specific, predetermined way forward.I

In her essay “Making Not Knowing,” visual artist Ann Hamilton defines unknowing this way:

One doesn’t arrive … by necessarily knowing where one is going. In every work of art something appears that does not previously exist, and so, by default, you work from what you know to what you don’t know….

But not knowing, waiting and finding—though they may happen accidentally—aren’t accidents. They involve work and research. Not knowing isn’t ignorance. Not knowing is a permissive and rigorous willingness to trust, leaving knowing in suspension, trusting in possibility without result, regarding as possible all manner of response…. Our task is the practice of recognizing.

Hamilton is writing about art, but she speaks truth about leadership. The unknowing leader is suspicious of her own experience. She doesn’t leave her knowledge at the door, but she is cautious about her own certainties. She invites the organization on a journey of discovery. She adopts a discerning mindset and invites others to join the expedition.

It is not the leader’s job to know the vision, or to bring it to fruition. The leader’s job is to nurture a state of wonder. It is the leader’s job to notice and articulate the collective yearning that emerges in response to wonder.

Releasing Fear, Cynicism, and Judgment

In Theory U, Otto Scharmer, writes about the perceptual biases (blind spots) that keep us trapped in tired ways of seeing. Scharmer identifies three internal voices that prevent a leader from living with open mind, heart and will: the Voice of Judgement, the Voice of Cynicism, and the Voice of Fear. Setting these voices aside is central to discovering fresh vision.

The Voice of Judgment is intellectual. It seals off the leader’s mind from imagination and creativity. This is the voice chattering incessantly about everything you know. It protects your mental status quo. “When I say this, they will respond with that. This is how my congregation works. What we really need to do is that.”

The Voice of Cynicism is born of mistrust. This voice wants you to believe that people act only from self-interest, which is always opposed to the interest of the organization. The voice of cynicism tries to protect you from vulnerability and doubt. It assumes the worst in others. “She will never support this idea. He always responds like that. What can you expect from a group of people who believe as they do?”

The third voice, the Voice of Fear, blocks the gateway to new possibilities. Fear wants to prevent you from letting go of what you have and to protect you from suffering any further losses. The voice of fear is instinctively suspicious of new ideas and risky ventures. “We don’t have the resources to pursue that. We can’t risk losing any more members. Our people just don’t have the energy to take on anything this bold.”

Releasing the voices of judgment, fear and cynicism requires listening with respect to what each of them has to say, then prayerfully releasing what is not helpful. Moving beyond fear, cynicism and judgment frees you to adopt a spiritual stance of wonder—an open stance that lets new possibilities emerge.

Finding yourself devoid of energy and vision in the new year isn’t a sign of failure. It doesn’t have to mean that you are used up and ready to move on. It is an invitation to examine your perceptual bias, to practice the art of unknowing, and to release the inner voices that keep you trapped in malaise. Discovering a new vision for your tired context may be as simple as swapping the lens through which you view your world.

Susan Beaumont specializes in the unique leadership needs of large churches and synagogues. Her areas of expertise include staff team health, strategic planning, size transitions, pastoral transitions and adaptive leadership. She is the author of the Alban book Inside the Large Congregation.[/box]