Around the world this fall, boards gather at their online tables to ask, “What kind of congregation can we be in this strange time? When and how can we return to ‘normal,’ and what will that even look like?” Some deny the possibility of planning in such times, but without deliberate planning, habit and momentum rule. Without structure, planning conversations run in circles or explode in conflict. At this time even more than most, boards need structured ways to talk about the future.

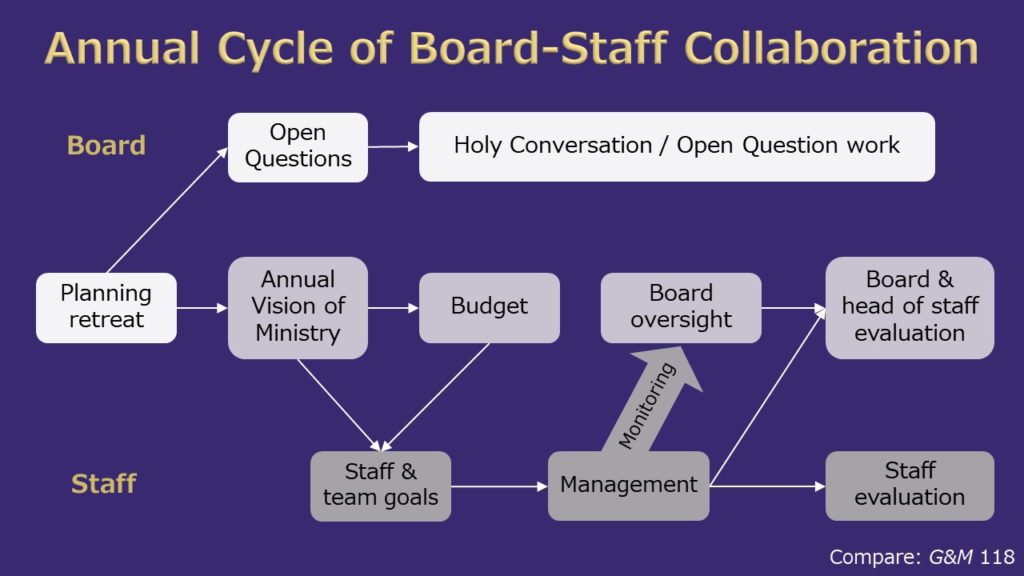

Updated “Annual Cycle” diagram

This is an updated version of a diagram in Governance and Ministry: Rethinking Board Leadership, 2d ed., page 118: A key annual event is the board’s planning retreat. The senior clergy leader always participates, and depending on the planning focus in a given year, the board invites others to participate as well. The retreat agenda …