Around the world this fall, boards gather at their online tables to ask, “What kind of congregation can we be in this strange time? When and how can we return to ‘normal,’ and what will that even look like?” Some deny the possibility of planning in such times, but without deliberate planning, habit and momentum rule. Without structure, planning conversations run in circles or explode in conflict. At this time even more than most, boards need structured ways to talk about the future.

Like the board of a business corporation, the job of a congregation’s board is to “own” the organization on behalf of its true ownership. In a business, that’s the stockholders. For a congregation, the true owner is its purpose or mission—the small piece of God’s will it exists to do. The board holds the congregation’s human and material assets in trust to ensure that all its efforts are directed toward the fulfillment of its purpose.

But how? Through a structured process of board-level planning, board and clergy leader make big choices about how the congregation will achieve its mission.

Three planning surprises

Boards that struggle with their planning role often are surprised when I point out three key truths about board-level planning:

Board planning is a partnership between the board and senior clergy leader. Some boards feel that they should plan on their own and then hand the result over to the clergy and staff to implement. In a mistaken effort to show respect for the board’s independence, some clergy stand aloof from the board’s planning process. The result, too often, is a plan that does not connect with the staff’s work, or even promotes conflict between the board and staff. For planning to have maximum impact, the senior clergy leader participates as a full partner with the board.

Board planning calls for a LONG time horizon. Board-level plans address major shifts in the congregation’s ministry. Such shifts affect annual budgets, capital fund raising, and building space requirements. This means that the plan a board adopts today must address a fiscal year whose budget has yet to be written. This fall, I’m helping boards to adopt plans for fiscal 2021–22. After the first of the year, I’ll be helping boards that budget on a calendar year to create plans for 2022.

Many board members are surprised initially to think so far ahead, but eventually they see that the board’s impact has always operated on at least this long a range—but it has done so tacitly. By not planning for the fiscal year beyond the current one, the board effectively decrees that no significant changes will occur until necessity compels them. A long planning horizon maximizes the board’s power to steer the congregation’s long-range course.

Planning is the board’s main function all the time. Many boards spend most of their time listening to reports, responding to complaints, and considering proposals from the staff and others. If they plan at all, it’s only on special occasions like an annual retreat, or by proxy through committees. No wonder board members end the year so frustrated! Planning engages people in creating a vision of the future based on insights about the congregation’s gifts and calling. The first sign of success at planning often is that board members get much happier and attend meetings more consistently.

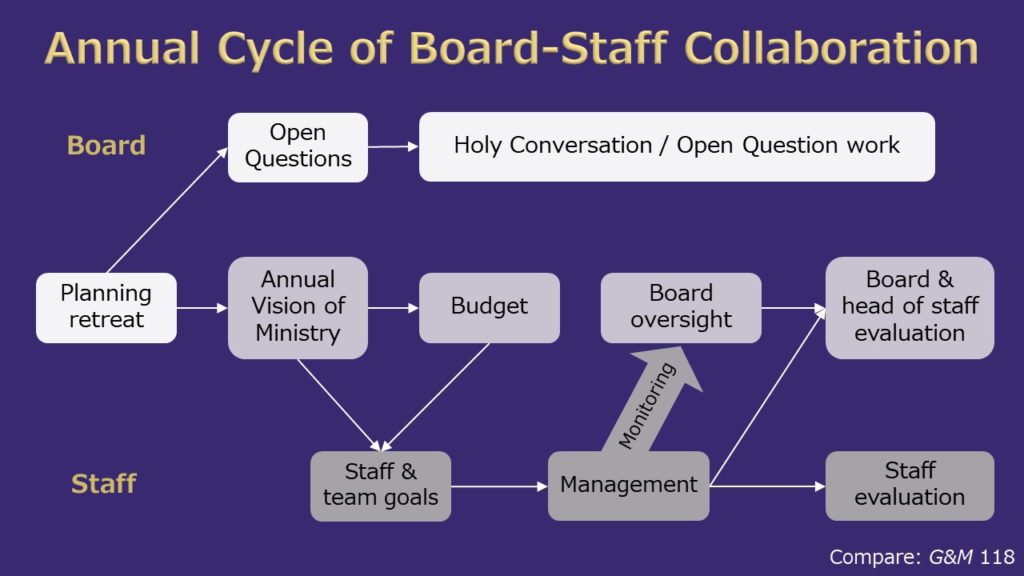

What does board-level planning look like? The diagram above describes my approach as described chapter 8 of my book Governance and Ministry. The process begins with an annual planning retreat that includes the board and clergy leader. Others may be included by agreement, but I find that the advantages of a smaller group generally outweigh the benefits of wide inclusion at this stage.

Two planning products

The board invites wider participation in planning by producing not one but two main products at the retreat each year. The first is an Annual Vision of Ministry that declares up to three strategic goals or priorities. These goals should be

- Not too big: “Eliminate racism in our city.”

- Not too small: “Encourage ushers to be nicer to Thai immigrants who visit worship”

- Just right: perhaps “Form partnerships with Black-led organizations to advocate for justice.”

Above all, each point in the Annual Vision must identify a true strategic choice—an option that the congregation chooses from among alternatives. The Annual Vision contains only goals the board is ready to hand over to the clergy leader to accomplish without further permission or excuses. When a budget is proposed later, the clergy leader should say, “I believe this budget will enable us to accomplish our Annual Vision of Ministry.”

The second product of the annual retreat sets the stage for wide participation in shaping the long-term direction. The board adopts a set of one to three Open Questions it will study for the year after the retreat. Like board goals, the Open Questions should be

- Not too big: “What would Jesus do?”

- Not too small: “Should we hire a Youth Minister?”

- Not too academic: “What attracts young people to church these days?”

- Just right: perhaps “What will our future ministry with youth and families become as we adapt to changes in the demographics of our region?”

Open Questions point to choices that might be addressed in future Annual Visions of Ministry. The Annual Vision guides the work of the staff; Open Questions guide the planning work of the board. The best Open Questions point to strategic choices among actual alternatives and invite discernment about what difference the congregation means to make in the lives of people.

Board-level planning all year long

Work with the Open Questions becomes a primary focus of the board’s work throughout the year, both at meetings and in conversations that the board convenes with others inside and outside of the congregation’s membership. The product of this work may be priorities in future Annual Visions of Ministry. Or it might be that through diligent reflection, data-gathering, prayer, and conversation, the board concludes that it asked the wrong question! Negative results like this can sometimes bear more fruit than any other.

Many board members dread board meetings, where they expect to spend time passively listening to reports, fielding complaints, or solving problems that could have been dealt with away from the board table. Many clergy dread board meetings, where they expect to be picked on, criticized, or condescended to without much benefit to the real work of the congregation. When boards move planning to the center of their agenda, the first benefit often is that board members get happier and board attendance improves.

Practical planning—done by staff and volunteers as they lead programs and operations—is always important. Board-level planning is different. It addresses the strategic question, “In what new and different ways will we transform lives in future years?” No board can answer this alone—and no one but the board can answer it with authority.

Dan Hotchkiss has consulted with a wide spectrum of churches, synagogues, and other organizations spanning 33 denominational families. Through his coaching, teaching, and writing, Dan has touched the lives of an even wider range of leaders. His focus is to help organizations engage their constituents in discerning what their mission calls for at a given time, and to empower leaders to act boldly and creatively.

Dan coaches leaders and consults selectively with congregations and other mission-driven groups, mostly by phone and videoconference, from his home near Boston. Prior to consulting independently, Dan served as a Unitarian Universalist parish minister, denominational executive, and senior consultant for the Alban Institute.