I’ve spent the last two years being angry.

To be fair, I wasn’t exactly not-angry before. My full-time job for the last decade has been providing food for low-income people. It’s hard to be anything but angry when so many Americans assume that anyone who needs food assistance is a lazy person making bad decisions. Most of the 17,000 people I serve each month are children, the elderly, people with disabilities, and people holding down multiple jobs—it’s hard not to be angry at the seemingly willful ignorance of those who believe otherwise.

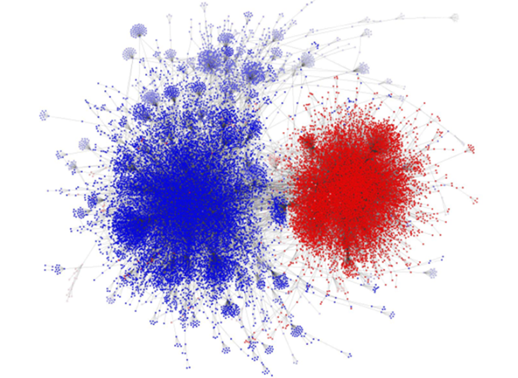

So I have become a textbook example of polarization—the topic my colleagues and I will spend the next few weeks talking about.

But there’s more to my anger than identification with the poor and hungry. Honestly, the two people in my world I worry most about are my own two millennial children. They work hard, have overcome enormous personal challenges, and are bright, good-looking, and valued by their professors, employers, and friends. But they have to worry about insurance and healthcare in ways I never imagined at their age, their debt load will haunt them beyond my lifetime, and they may never be financially secure.

And then—of course—there’s our present environment of narcissistic fear-mongering, re-emergent racism and sexism, and climate change.

The angry leader

So I’m angry—and my anger is not free-floating. It’s directed at specific groups of people whose behavior, including voting patterns, I believe to be responsible for all this pain.

Nor is it occasional—anger beats with my heart, colors everything I see, and is the rock shelf that undergirds my every move.

Fortunately, at least for the people around me, I don’t get to express all this anger. I have a job, and, like most people, my success depends on being able to control myself.

And while others may be angry, too, we don’t agree on who’s responsible for our fear and pain, so we have to figure out how to get along.

And most importantly, I don’t want to live with this much anger. It’s not good for me or the people around me. So, as addictive as anger is, I’ve had to develop alternative ways to deal with my fear and pain.

I’ve found safe places to say what I actually believe. I can’t express how affronted I am by the behavior of our leaders and just swallow my feelings, so I cultivate relationships with people with whom I can be honest.

Calm role models

I try to behave as if I felt differently. Many years ago, as a young professional, I encountered my first bullies among the members of my congregation. I felt scared and defeated, but I didn’t want to look as weak as I felt. I identified community leaders who seemed to be thriving under similar pressure and I imitated how they behaved, even though it didn’t match how I felt. Essentially, I imagined a confident version of myself in my head and behaved like that person rather than like my scared self. That way, I could keep showing up when what I wanted to do was curl up in a ball and hide. In the same way now, I ask myself, “How would someone act who’s feeling calm and rational rather than furious?” and then that’s what I do.

I get more sleep. For the last few months, I’ve been aiming for seven to eight hours a night rather than my usual six, and it’s surprising how much better I feel.

I listen to my own sermons. For 10 years in the 1990’s, I preached every Sunday at the same church. Now I supply preach, which means I’m usually recycling a sermon from those years that I don’t even remember writing. Last week, I unexpectedly teared up as I reached the end of a sermon about the ways God keeps God’s promises of peace—even when the world does not seem peaceful. I think one part of my brain was preaching while another part was hearing something new that it needed to hear.

The silver fish

I watch for “the flicker of a silver fish in a dark pond.” These words, uttered by Phyllis Tickle many years ago in a Sunday School class she led for me, describe perfectly how the Holy Spirit can makes itself known—if we have eyes to see.

Two weeks ago, I caught a glimpse of that silver fish as I was watching John Dickerson interview jazz pianist Jon Batiste. Batiste talked about the way a jazz artist creates space between the notes, space that lets the listener slow down, breathe, and consider what just happened. Space allows the hearer to experience a familiar song anew. As Batiste played and spoke, I glimpsed a new possibility for how I might respond to fellow anger-sufferers from across the polarized divide—not with quick flashes of fury but slowly—by creating space.

I am as enmeshed in our current state of polarization as it’s possible for anyone to be. But those of us who are leaders cannot stay here. One word, one hour of extra sleep, one musical note at a time, we have to find a way out – and support each other in our journey.

[box]Sarai Rice consults with congregations on a variety of issues including planning, program development, and governance, and offers coaching for clergy and lay leaders. She has a passion for work across the lines of faith traditions, especially in areas involving community ministry and social justice, as well as a deep commitment to the notion that human institutions should work well for the people they serve.[/box]