Amid the conflicts and tensions that arise in congregations, we have more than enough opportunities to act on impulse. Too often, especially when we are upset, we lock into a reactive tug-of-war: “Yes, you did!” “No, I didn’t!” Before long, we’ve said something that we wish we hadn’t. Escalation seems inevitable, but instead of getting into a contest, we can simply—in the words of recent meme—“Keep Calm and Drop the Rope.”

Dropping the rope is an excellent temporary strategy. It helps create some distance between the heat of a tense situation and ourselves. It can help our responses to be less “reptilian,” and allow us to shift out of reactivity into responsiveness. Lowering the temperature in ourselves or in the situation that we are engaged in might be just the thing that is needed—temporarily.

The problem comes when dropping the rope becomes an escape route rather than a path to creative engagement or responsiveness. With our emotional system cooled down, the temporary relief is satisfying. But running away from tension can be just another automatic impulse. It’s what we do after we drop the rope that matters.

Expanding Our Repertoire of Responses

I studied family systems theory—Murray Bowen’s approach that analyzes human behavior using the family, not the individual, as the primary emotional unit—in my pre-ministerial training as a therapist. But it wasn’t till my first few years as a minister, when I read Generation to Generation: Family Process in Church and Synagogue, by Rabbi Edwin Friedman, that I made the connection between what I was experiencing and Bowen Theory. In my original copy of Friedman’s book, I wrote many marginal notes illustrating what he offered in his pages. When he did a series of seminars in the Boston area, I sat in the front row as a devotee, grateful for how he integrated two of my worlds: psychotherapy and congregational life.

Over the years, I have found that, in addition to help learning self-differentiated leadership and analyzing the emotional system of the church, my clients also need practical tools. I now use an assessment, the Conflict Dynamics Profile created by Craig Runde and Tim Flanagan, to help clients (a) recognize their emotional triggers, (b) understand their typical responses to stressful situations (c) expand their repertoire of responses.

Once we’ve “dropped the rope” and lowered our own anxiety, we need to develop practical strategies. I have found that clients’ self-assessment (or 360-degree assessment) on the Conflict Dynamics Profile helps them to “see” themselves more clearly. With these insights, we can develop a personal development plan that makes it possible to try “experiments” in everyday actions as we broaden the repertoire of available responses.

Becoming a Conflict Competent Leader

To be a conflict-competent leader means to be able to draw on a wide repertoire of responses in the face of tension. Because we each heat up in different ways and have our own “hot buttons,” it is crucial for us to learn about ourselves:

- What are our current constructive responses to conflict?

- What behaviors do we engage in more readily when we discover we are in a situation where differences and tensions emerge?

- What are our current not-so-constructive or even destructive responses to conflict?

- What behaviors do we tend to engage in that tend to continue to heat us up or raise the heat in the situation?

- What kind of interactions move us toward resolving workable issues and which simply aggravate them?

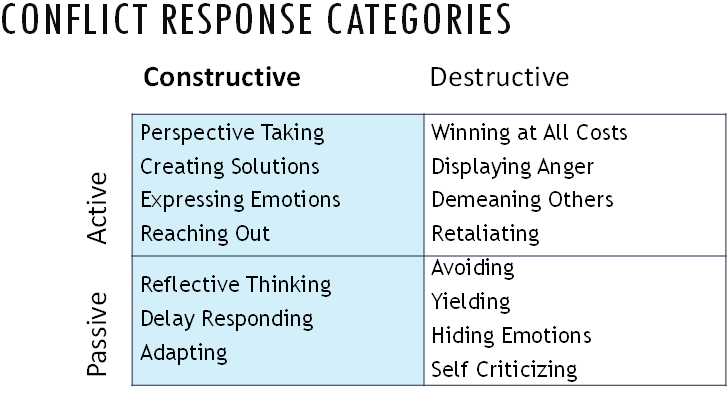

What I’ve particularly liked about using the Conflict Dynamics Profile with individuals and teams is that the instrument distinguishes not only between constructive and unconstructive behaviors, but also between active or passive ones. One constructive–active behavior is “perspective-taking,” such as saying “Could you explain to me why this is so important to you?” Or, “What in your experience that has led you to this conclusion?” An example of a passive–constructive behavior is “delayed responding,” which is a form of “Dropping the Rope.”

Constructive responses can easily shift to not-so-constructive when instead of being open to another’s perspective, we engage in behaviors of “winning at all costs,” or instead of adapting, we avoid engaging with the situation at all.

Caring for the Climate

Through trauma-informed practice, we attend better to how our personal history causes certain incidents to be more “triggering” to us than others. With some of my clients I explore the ‘biography behind their biology”—how our bodies take in past events and sensitize us to our “hot buttons.” With this awareness, we can then rehearse constructive, cooling-down strategies when we anticipate encountering a triggering situation.

Each organization or team has its own profile in managing differences and conflict. The behavioral approach of the Conflict Dynamics Profile can serve as an awareness tool, providing each person and team an opportunity to expand their repertoire of responses.

In a time when so many of our common issues as religions, as a society and a globe require seeking common ground and collective action, we need to find ways to engage tensions constructively and connect across differences. We need to find ways to interrupt patterns of interaction that divide people. Instead, we can learn and practice new and constructive ways of responding.

Lawrence Peers is dedicated to serving and coaching leaders and teams from a comprehensive and integral perspective. His focus is on helping leaders be a better observer of their own leadership and of the organizations they serve in order to design skillful and reflective leadership responses. He is a Professional Certified Coach (PCC), certified Leadership Circle ® coach and Immunity to Change® and Conflict Dynamics Profile® facilitator and a Strozzi Institute Associate. He was a former director of the Pastoral Excellence Network and continues to provide training to clergy coaches and mentors. He is an adjunct professor at Lancaster Theological Seminary and Hartford International University for Religion and Peace focusing on adaptive leadership, conflict transformation and spiritually-grounded leadership.