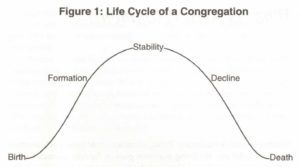

Most of us who do church work are familiar with the notion of the congregational lifecycle. It’s a bell-shaped curve: starting at the left with birth, congregations move through formation to reach peak stability. Then they start to move back down toward decline and ultimately death—unless we do something to change the curve.

I first encountered the lifecycle in Alice Mann’s 1999 classic, Can Our Church Live? I’ve taught about it many times and I believe it’s accurate, but I’ve begun to wonder if the curve’s gift might also be its curse.

It’s true that congregations, like humans, are born at a particular moment and eventually come to an end. (I don’t know of any congregation—much less any person—that is still around after 2000 years.) I’ve sometimes seen the curve reshaped to reflect differing energy levels, with a quicker peak after the birth because that’s where the excitement happens, followed by a much longer tail reflecting the slow waning of declining congregations.

Gift or Curse?

based on work by Robert Saarinen, Arlin Rothauge, and Robert Gallagher

The curve’s gift is that, like any good visualization, it’s easy to understand. Congregations can almost always place themselves on the curve.

But I’m beginning to wonder if the curve’s gift is also its curse—that once a congregation places itself on the downward side of the curve, it comes to believe decline is inevitable. Consultants and preachers talk about the need to respond with adaptation and new energy and revitalization, but what people internalize is that downward line.

Is there a different way to tell the story of a congregation that doesn’t draw everyone’s eyes downward?

I started thinking about this question last week while writing a children’s sermon. The point I was trying to make is that the Bible looks like a book—in this case, Eric Carle’s The Very Hungry Caterpillar—with a clear beginning (creation/caterpillar), a clear narrative arc (salvation history/eating everything in sight), and a clear end (second coming/butterfly). But really the Bible is composed of thousands of large and small preexisting bits—laws, hymns, novellas, prophetic utterances, letters—woven together by different people over time. The Bible’s “story” can be told differently depending on which bits the reader finds most interesting or chooses to assemble into a narrative arc.

Lemon, Lemur, Lizard

To illustrate this point, I gave the children a set of picture tiles—a lemon, a lemur, a lizard—and asked them where the story started. They soon saw that the story could “start” with any picture and proceed in any number of ways.

A story about lemons unfolds differently if we allow for the unexpected lemur. Might a congregation’s story play out differently if we began not by reciting a fixed narrative of decline but by expecting unexpected hope? What if we knew that there might be a lemur?

As a result of COVID-19, we all are participating in this kind of serendipitous storytelling. The pandemic was unexpected by all but the most knowledgeable public health experts. None of us were factoring it into our strategic plans. Its most obvious results have been conflict, anxiety, and relentless stress. After more than a year of trauma, simple requests have become harder to fill, minor disagreements are harder to negotiate, and plans that looked possible yesterday have come undone today.

Unexpected Gifts

But unexpected gifts have emerged as well. Even the smallest congregations have figured out how to show up in new ways in members’ homes, whether with advanced technology or red balloons for Pentecost. We’ve rediscovered the joy of worshiping outdoors as Jesus did, although in our case it’s more likely to be in a parking lot than on a riverbank. We’ve taken time to reimagine and repaint or scrub our spaces thoroughly so they’ll be ready when people return. As individuals, we’ve learned we can be loyal to our congregation while still tuning in to worship or Bible study anywhere at any time. Church has changed, and so has our experience of it.

Human beings are not new at reinvention. The increased life expectancy that came with modern medicine, for example, has led to a different understanding of our later years. Far from expecting retirement to be filled with sadness and infirmity, we now see it as a time of possibilities. We learn new things, go new places, meet new people. We make space in our lives for excitement, joy, and new challenges. Congregations see the result of this new approach all the time in retired church members who no longer are available for every kind of volunteer work because they have too many new adventures to live.

Expecting Lemurs

What would happen if—instead of identifying our place on the downward curve of the church lifecycle and anticipating sadness and decline—congregations foresaw a time invigorated by new challenges? What if we assumed the future will be filled with joy and new adventures? What if we were confident we can take the pieces we are handed and put them together in any number of ways? What if we expected lemurs?

Free to tell our story in new ways, I can’t help believing we can find ways to reimagine our lifecycle curve and turn it into something new.

Sarai Rice is a Presbyterian minister and a retired non-profit executive. She consults with congregations on a variety of issues, including planning, staffing, and governance. Sarai loves to work with congregations that are exploring anew their role in the community as well as congregations seeking new energy in the face of decline. She has a deep commitment to the notion that human institutions should work well for the people they serve.