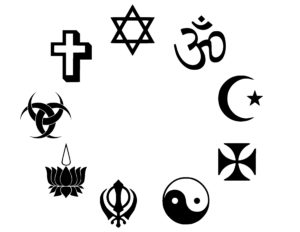

At a time of year when we turn our personal and national attention to reasons for gratitude, I want to give thanks for something that doesn’t always make my list—I am grateful for religious diversity.

At a time of year when we turn our personal and national attention to reasons for gratitude, I want to give thanks for something that doesn’t always make my list—I am grateful for religious diversity.

It doesn’t always make my list because I’ve always been able to take it for granted. My father’s officemate was one of the few Jews in Kirksville, Missouri in the late 1960s and 1970s, and he ate with us every Friday night. My father’s students included Muslims from Turkey and Iran who lived in our home and taught us to cook. We were raised Presbyterian, but we lived interfaith.

Fifty years later, I still live in an interfaith environment. I manage an interfaith non-profit whose members are congregations of the Jewish, Christian, Muslim, Buddhist, and Unitarian faith traditions, and we feed people in the name of our shared commitment to our neighbors, not in the name of a particular understanding of the divine.

Crossing Lines of Faith

Not everyone in so fortunate. Just last week, I met with Professor Simangaliso Kumalo of the School of Religion, Philosophy, and Classics at the University of KwaZulu-Natal in South Africa. He is in this country in part to share his dream for an Institute of Religion, Governance, and the Environment, where students would be trained in the intersection of religion and environmental policy. What struck him about our work here in Des Moines was our focus on feeding the hungry as an act of interfaith relationship. Christianity is a dominant tradition in his region, and he finds that his fellow Christians there have almost no interest in engaging with other faith traditions for any reason.

In this country, however, we are the beneficiaries of thousands of individuals who have devoted their time to understanding the stories and practices of people of faith traditions other than their own.

Eboo Patel, in his book Interfaith Leadership: A Primer, tells the story of Ruth Messinger, former president of American Jewish World Service. An observant Jew from New York City, Ruth found herself directing child welfare programs in western Oklahoma in the late 1960s. Because she needed foster homes for children in her area, she started knocking on the doors of evangelical Christian homes and congregations. Patel reports that Ruth “sat through countless sermons, praise songs, and altar calls,” waiting for the opportunity to speak. Whenever the preacher gave her a chance, she would tell stories of the challenges faced by troubled youth and express her hope that they would find loving homes. When she was done, the preacher would ask who was willing to help, people would literally line up.

Patel tells Ruth’s story to illustrate how interfaith leaders seek connection rather than division:

Ruth found ways to speak to and mobilize a different religious community for a common cause. She learned to build trust with the pastor. She learned to earn goodwill by paying personal visits to house-churches and spending time with the people who gathered there. She even learned that being a new mother with a little baby provided an initial point of positive contact.

In my own organization, the Des Moines Area Religious Council, we tell similar stories. DMARC was limited to Christian congregations until the 1970s, when some members of the local Jewish community, including local attorney Larry Myers and engineer David Bear, agreed to serve on the boards of the Council and its Foundation. Because of their willingness to attend meetings, offer wisdom, and make contributions, the organization was able to move beyond its ecumenical roots and toward creating a safe space for believers of all faiths, including atheists and others who have no “faith.” DMARC stood with the local Reform temple, for example, when it was defaced with antisemitic graffiti 20 years ago.

Interfaith work yet to do

But as grateful as I am for the hard work, grace, and goodwill of the interfaith leaders who have come before me, there is still so much to do. Blatant acts of antisemitism and hate speech are once again on the rise. The majority of Americans would still not knowingly vote for a presidential candidate who is an atheist. And it is increasingly clear that members of a dominant culture, whether they be white, male, or Christian, have a hard time seeing the extent of their own privilege or recognizing the shape of their own bias.

Even worse, it now seems to me that some of the activities we have promoted over the years in an effort to teach about other faith traditions have had the unintended effect of treating people of those traditions as objects of our scrutiny rather than as the subjects of their own lives. I now find myself wondering how it feels to members of the host community when I take my youth group to a Sabbath observance at a local temple or a time of prayer at a Sikh Gurudwara.

Gifts of diversity

Religious diversity is a gift. Even for those of us who are profoundly convinced of the “rightness” of our tradition, conversation with people of other faiths often provides moments of startling insight, not just into the beliefs and rituals of those who think otherwise but into the deepest heart of our own beliefs. We should be grateful for every individual who has spent or continues to spend time drawing us closer to each other.

But now is not the time to leave this work to others. As our congregations write their needs assessments and strategic plans, we need to realize that the work to God calls us may not always be to build bigger buildings or even better food pantries. Sometimes the call may be to spend time with our Sikh, Hindu, Jewish, Muslim or Unitarian brothers and sisters down the street—not just to learn about them or even to ensure that we will recognize each other in times of crisis, but to build a sacred space together where we can honor one other’s differences.

[box]Sarai Rice consults with congregations on a variety of issues including planning, program development, and governance, and offers coaching for clergy and lay leaders. She has a passion for work across the lines of faith traditions, especially in areas involving community ministry and social justice, as well as a deep commitment to the notion that human institutions should work well for the people they serve.[/box]