How is a pastor like a forklift operator? Not very much, apparently. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), the jobs of clergy and equipment operators are about as different as two jobs can be. If you’re a clergyperson and your board is full of forklift operators, this fact might help explain why you are feeling lonely!

How is a pastor like a forklift operator? Not very much, apparently. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), the jobs of clergy and equipment operators are about as different as two jobs can be. If you’re a clergyperson and your board is full of forklift operators, this fact might help explain why you are feeling lonely!

Work shapes us in many ways, but in congregations we don’t talk about it much—for reasons some of which are good. In God’s house, we want everybody to feel equal, and one way to deal with inequality is simply to avoid talking about work. But I think it would be better to encourage gentle conversation about the diverse ways work forms our spirits. This would be good for everybody, but perhaps especially for us clergy.

Types of work

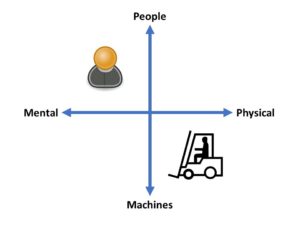

A fascinating chart, published by the BLS and reproduced by the New York Times, ranks hundreds of jobs according to their emphasis on physical or mental work, and by their emphasis on serving people versus operating machinery. The chart is meant to help people who have lost their jobs to find new ones that require similar (or different) skills. It could be an interesting conversation starter for a faith-formation group.

Forklift operators live at the lower right-hand corner of the chart as solitary operators of machines. Clergy occupy the upper left—thinking abstract thoughts about men, women, children, gods, and other non-robotic entities, and tending personal relationships with and among the human beings in their care.

Stereotypes? Simplifications? Of course. No chart can capture the complexity of work. Not all forklift operators are alike. Some, no doubt, read Proust during breaks. I once worked in a machine shop where the breaktime conversation always touched on opera. Joe and Homer—master machinists for whom opera was a popular art form from the old country—watched public television and had opinions about every diva.

On the other end of the spectrum, I once knew a contractor who became a Presbyterian minister, but never quite completed the career change. His church had a fleet of jobsite trailers in the yard, ready to load up with Presbyterians to go help people in disaster zones. You can’t judge a book by its cover—or know a human being by a job title.

Still, so many of us spend so much of our lives at work, we inescapably absorb a lot of what we know and who we think we are from the jobs we do. Work influences our worries, and especially our worries about job security. Tellingly, the BLS chart color-codes jobs to show which are most at risk from automation.

Fear of automation

The more physical a job is, the more likely it can be replaced by a machine. The ranks of stonemasons, fishers, and machinists, to name just a few, are thinned already as machines take on more work. Food servers, office clerks, welders, and warehouse workers all are at high risk. In addition to the culture-shaming that accompanies a low income, workers in these categories have to worry about being on the wrong side of the history of technology.

Next in line for automation are workers who use their hands to produce highly customized results. Surgeons, architects, and car repairers use machines for chores that once required professionals: MRI machines replace exploratory surgery, CAD tools draw up building plans and even check them for mistakes, and automated factories stamp out car parts for repair shops to snap in when diagnostic software tells them to. We’ll always need some high-skilled craft workers, but possibly fewer as technology increases each one’s productivity.

Workers have long worried about automation, but it’s hard to remember when whole occupational categories were at such risk, especially in what were once high-paid, secure professions. It’s a pastoral concern we can’t address without making it OK to talk about our work—and the worries that go with it.

Clergy at work

Clergy do not come into this conversation as objective outsiders. Our jobs primarily require “people skills,” and so might seem quite safe. But not so fast: retail clerks, technical support specialists, lawyers, car salespeople, and taxi drivers all have seen some of their people-oriented jobs replaced by smart machines. In the last century, the same thing happened to elevator men and “hello central” operators.

Clergy worry too about our job security, and part of our concern arises from technology. Some aspects of the work of clergy are already automated, in the sense that people can hear preaching on TV and form communities of faith online. The rise of larger congregations is abetted by technology: large screens bring the pulpit closer to the back rows of an auditorium and communication is much easier now than in the days of the mimeograph.

More broadly, clergy face the heightened competition all “performers” do—like comedians, musicians, politicians, and magicians, we face audiences that can compare us to the very best. Thirty years ago, my congregation experimented with a hearing-assist gadget that used standard FM frequencies. Mr. Hockert, the one old man who agreed to try it, liked to say he was the only member of the congregation who could change religions just by turning a dial. Now, everybody can.

If talking about work is still taboo in your community, it’s time to lift the ban. Without ignoring the role work plays in establishing the hierarchy of wealth and power in society, and without letting go of our egalitarian principles, we can ask, “What did you learn at work that might be helpful to our conversation here?” and “What did you learn at work that might not be helpful?”

Many of us learn too much at work and not enough at home, in our neighborhoods, or in our communities. But in congregations, our anxieties can be embraced, shared, and transformed. One way to start that process is with gentle conversation about work.

[box] Dan Hotchkiss consults with congregations and other mission-driven groups from his home near Boston. He is the author of the best-selling Alban book Governance and Ministry: Rethinking Board Leadership, which has helped hundreds of churches, synagogues, and non-profit organizations to streamline their structure and become more mission-focused and effective.

Dan Hotchkiss consults with congregations and other mission-driven groups from his home near Boston. He is the author of the best-selling Alban book Governance and Ministry: Rethinking Board Leadership, which has helped hundreds of churches, synagogues, and non-profit organizations to streamline their structure and become more mission-focused and effective.

[/box]