Congregations currently face many choices: How and when will we begin to gather in person for worship and indoor activities? What kind of worship, education, and outreach makes sense, after all that young people and adults have been through? Which postponed projects should take priority in this time?

Governing boards know they should be giving leadership, but many don’t know how. Instead, they spend their time as they did before: listening to reports, delving into the details that interest them, rehashing conversations they and others have had before.

What Governance Is Not

It’s not surprising that governing board members feel overwhelmed—it’s more than they can manage. Luckily, it’s not the governing board’s job to manage anything. Their job is to govern—to point the way and authorize others to act. What is governance? First, let’s take a moment to recall what governance is not:

- Governance is not listening to reports. To be strategists, board members need information to help them choose a future for the congregation. But reports inform them mostly about the past. A good goal, in my opinion, is to spend zero board time listening to reports—including reports from the senior minister or rabbi. If the board needs to discuss an issue, it can come as part of the board’s agenda—not as a subhead in a report from elsewhere. As a bonus, you’ll make board meetings less excruciating.

- Governance is not brainstorming how things might be done. The board’s job is to decide what should be done, not to generate ideas about how to do it. A board that clearly chooses the results it wants can charge the head of staff with finding ways to make them happen. Inevitably, when a board talks about the outcomes of the congregation’s work, some members will need to approach it by way of concrete examples, stories, and suggestions. But the board needs to return to its main task, which is to say what kind of community the congregation is called to be and how it means to change the lives of those within its reach.

- Governance is not lobbing potshots at the pastor—nor praising and applauding. Lay and clergy leaders need to think together about the big choices facing them and how they should respond. Pastoral feedback and evaluation is important, but it should not be a regular feature of board meetings.

If they remove these items, many boards find that their agenda has large gaps in it! What should they do with all that newfound time?

What Mission Statements Can and Cannot Do

One popular approach has been for the board to write a mission or vision statement. A congregation’s mission is important—I’ve gone so far as to say the mission is the congregation’s owner. But the mission and a mission statement are two different things.

Writing mission statements can be clarifying, even unifying. But the statement itself, too often, turns out to be a list of everything the congregation does, or might do. Or it might consist of pithy slogans that could have been written by a marketing consultant.

Both of these kinds of statements have their uses. But if I had to choose between a congregation with a perfect mission statement and a congregation whose leaders are all focused on achieving two or three priorities each year, I’d choose the latter.

The Board’s Main Job: Envisioning the Future

That’s why I try to help boards spend more time on planning—thinking about the future. The main job of the board, especially in a time of rapid change, is to discern, envision, and select a few areas where they intend to take a big step forward. The timeframe for board planning is not weeks or months, but years.

It might be objected that—in this time especially—no one knows what will happen in a month, much less a year. How then can we plan realistically? If we were talking about a traditional plan, with many pages of objectives, benchmarks, and detailed budgets and timetables, I would agree—but then, I’ve never found that kind of planning very helpful.

Helping the Board to Focus

To focus on the future, most boards need to take a few straightforward steps:

A first step is to remove timewasting agenda items. I’ve listed the main non-governance timewasters above. You can discover others by reading a few years of your board’s minutes. But it’s not enough to subtract from the agenda, because nature abhors a vacuum: if you don’t give the board compelling, interesting work to do, it will revert to its old habits.

A second step is to choose a timeframe for the board planning cycle. Boards that want to take a baby step might lay out a few goals to be accomplished in the coming year. That’s a good start, but for mature boards, I suggest focusing on fiscal years yet to begin.

Better yet, aim even farther out on the horizon, so the goals can influence the budget. For congregations whose budget year begins July first, that means the board must plan much farther ahead than most boards are accustomed to. The timeframe looks like this:

| Spring 2022 | Board begins developing goals for 2023–24 |

| Fall 2022 | Board finalizes 2023–24 goals |

| Winter 2023 | Staff develops budget, staffing plan, and capital plan to implement the 2023–24 goals |

| July 1, 2023 | Staff implements 2023–24 goals |

Because the planning cycle takes more than a year from start to implementation, its pieces overlap. As soon as the board finalizes its goals in the fall, it can begin thinking about goals for 2024–25. The kind of goals I’m talking about are clear but general. They say what difference the congregation means to make in people’s lives, allowing for a wide range of possible methods for achieving those results. They might say,

“By the end of 2023–25, we aim to become better allies to Black people in our city.”

“We mean to grow in our awareness of the lives of people living near our church campus.”

“Our church will become a better home for people with disabilities and chronic illnesses.”

At first glance, goals like these might sound like platitudes, but they represent real choices. The congregation will do lots of other things, but the board is naming a few areas where it expects to see major steps forward. By naming two or three such goals each year, boards can exercise a powerful and lasting influence on congregational life.

Allocation of Board Time

A third step is to plan the board’s agenda a full year in advance. Too many boards plan their agendas hastily, one meeting at a time. The old familiar structure of reports, old business, and new business (based on Robert’s Rules for large assemblies) becomes a substitute for intentional and caring use of members’ time.

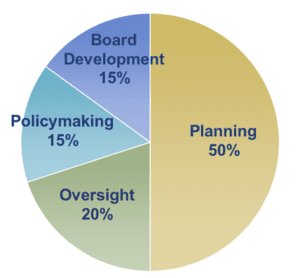

Here is how my ideal board would spend its time:

By planning its agenda far ahead, a board can appoint ad-hoc committees to prepare for each board meeting. Instead of a predictable sequence of reports, complaints, petitions, and approvals, each meeting centers a nutritious topical discussion. For example:

- Planning. Developing a short list of Open Questions and using them to help the board to think about goals for a future year. (50%)

- Oversight. An annual discussion with the senior clergy leader about how they and the board have worked together, whether goals have been achieved or not, and how the partnership of board and clergy can be strengthened. (20%–more if the clergy leader is new or if there are serious performance problems)

- Board Development. A seminar led by an outside expert to enable every board member to understand our congregation’s finances. A seminar to deepen the board’s understanding of its role, or of a mega-issue touching on the congregation’s long-term life such as racism, urban planning and development, religious, theological, and generational change, etc. (15% or more if possible)

- Policymaking. Ensuring that board policies are adequate to regulate the daily operations of the congregation, making it clear which buck stops where so the board can safely hand management over to the head of staff. (15%, once a good set of policies has been adopted)

When boards focus on the future rather than the past, discernment rather than self-criticism, and strategizing rather than reacting, the first people to get happier are the board members themselves. Meetings become livelier, relationships get richer, and the time spent feels worthwhile.

The first people to feel stressed when boards become effective are the staff, including volunteers who work as staff. Leaders used to being praised for simply carrying on feel pressured to produce actual results. That’s stressful in the short run, and some leaders will opt out. But in the long run, an effective board can energize the congregation and attract leaders who thrive on making a real difference in the lives of people.

And that is the board’s job—not to manage or coordinate the congregation’s work, but to say what difference the congregation means to make in people’s lives and focus leaders’ attention on making that happen.

Dan Hotchkiss has consulted with a wide spectrum of churches, synagogues, and other organizations spanning 33 denominational families. Through his coaching, teaching, and writing, Dan has touched the lives of an even wider range of leaders. His focus is to help organizations engage their constituents in discerning what their mission calls for at a given time, and to empower leaders to act boldly and creatively.

Dan coaches leaders and consults selectively with congregations and other mission-driven groups, mostly by phone and videoconference, from his home near Boston. Prior to consulting independently, Dan served as a Unitarian Universalist parish minister, denominational executive, and senior consultant for the Alban Institute.